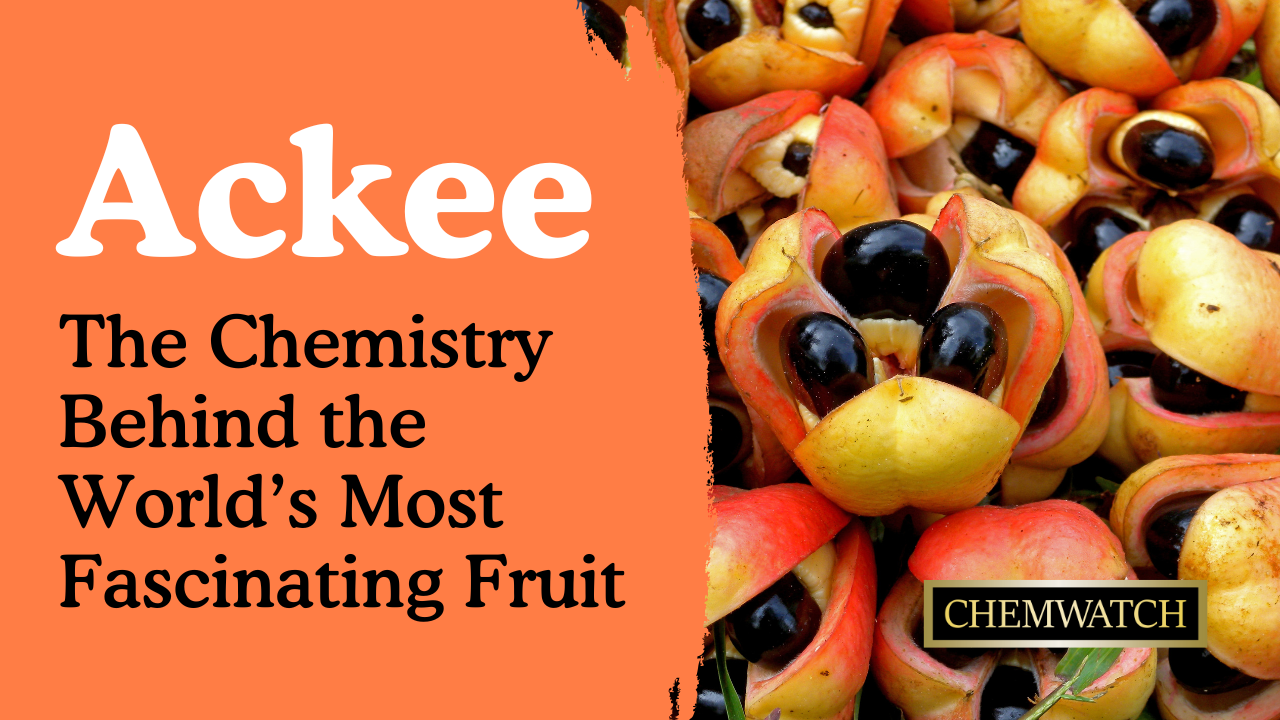

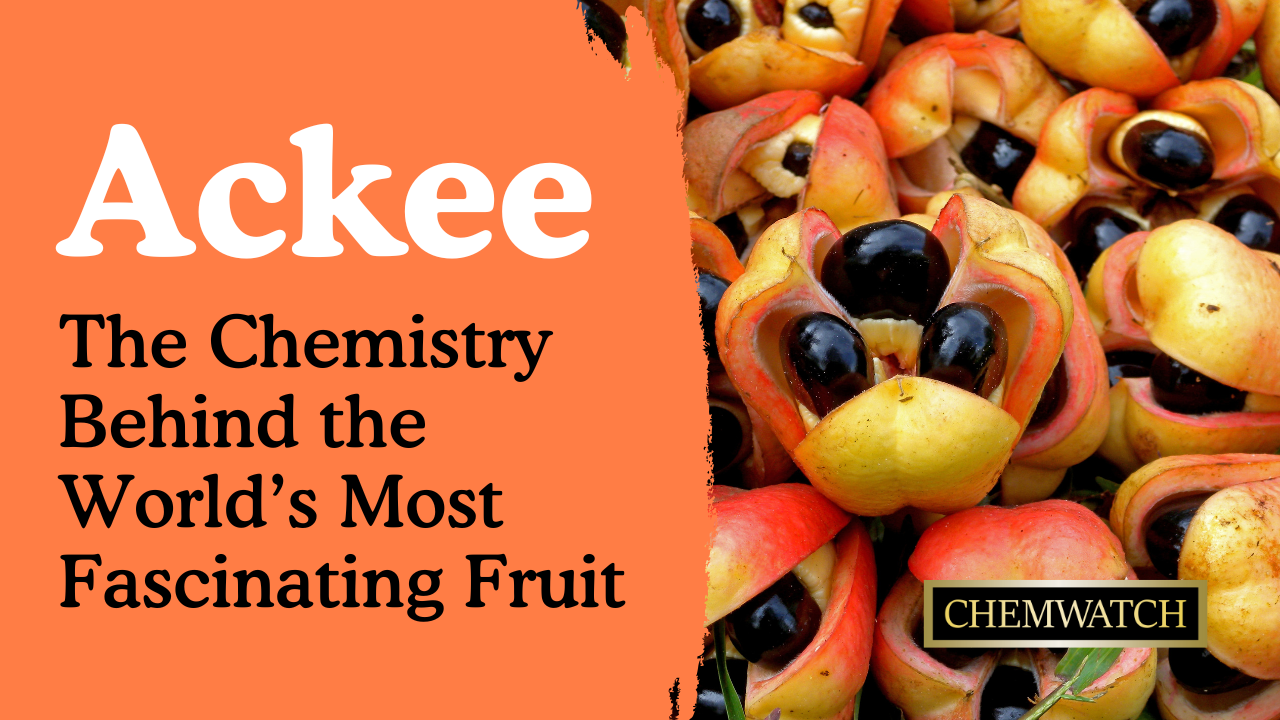

We wouldn’t be anywhere without modern advancements in agriculture and selective botany. Fruits come in a variety of shapes, colours, sizes, and flavours, but there is one fruit that stands out—not only for its culinary appeal but also for its chemical complexity. Meet Ackee (Blighia sapida)—arguably the world’s most intriguing fruit—used widely in Caribbean cuisine, yet known for its potential toxicity.

Despite its unique buttery, nutty taste, ackee has a dangerous reputation due to the presence of hypoglycin A and B, toxic compounds responsible for Jamaican Vomiting Sickness (JVS). However, when properly ripened, an enzymatic process significantly reduces its hypoglycin content, making it safe for consumption. Let's explore the chemistry of ripening, toxicity risks, and essential safety precautions when handling ackee.

Yes, you heard that right—unripe ackee is highly toxic. When unripe, hypoglycin A and hypoglycin B exist in dangerously high concentrations, making ackee consumption potentially fatal. However, as ackee moves through its ripening process, a natural enzymatic process occurs, significantly reducing hypoglycin A and B content and transforming the fruit’s arils from hazardous to harmless.

This enzymatic process is crucial in determining whether ackee is safe to eat. After properly ripening, ackee naturally opens, revealing its yellow edible arils and dark exposed seeds—a clear visual cue that the fruit has transitioned into a safe-to-consume state.

Hypoglycin A is a toxic amino acid that interferes with fatty acid metabolism, inhibiting medium- and short-chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenases—and this toxicity results in Jamaican Vomiting Sickness (JVS). JVS is a severe condition characterised by hypoglycemia, vomiting, convulsions, and even fatality in extreme cases.

Scientific research has shown that hypoglycin B also contributes to ackee toxicity, though its role is less potent than hypoglycin A. The combination of these toxins in unripe ackee makes proper ripening and preparation essential to avoid the dangers of ackee poisoning.

Despite its toxic risks, ackee is widely consumed in Jamaica, where it is the national fruit and a key ingredient in ackee and saltfish—Jamaica’s national dish. Ackee is also commonly consumed in Haiti and Belize, and in West Africa and parts of the Caribbean, ackee has other uses, including for soap properties, fish poison, cologne, construction, and for traditional medicine for minor illnesses. Being used so widely in these parts of the world, the distinct appearance of ripened ackee helps locals easily identify safe fruit for consumption.

To protect consumers, strict safety precautions and regulations are enforced:

Understanding ackee toxicity and following safety precautions and regulations allows consumers to enjoy its culinary benefits without risk.

At Chemwatch, we specialise in Safety Data Sheets (SDS) to help businesses manage chemical risks effectively. Whether you're dealing with food safety regulations, toxicology concerns, or compliance requirements, our SDS solutions provide:

If you're looking for expert guidance on chemical safety and compliance, Chemwatch is here to help. Contact us today to learn more about Safety Data Sheets (SDS), regulatory requirements, and best practices for handling potentially toxic substances.

Stay safe and stay informed. Get your SDS from Chemwatch!

Sources