Feathery, talony, chirpy or squawky—birds are often a regular fixture of daily life. From the humble city pigeon and moody magpie to the seaside gull and high-flying falcon, there’s a good chance you see or hear a bird at least once a day no matter where you are.

They come in all shapes, sizes, and demeanours, with some louder, livelier, and more lovable than the next. And then there are the others. The wonderful, wild and the downright weird. You are unlikely to see these fellows on your daily dog walk, so we’ve rounded them up for you to take a gander. Read on to discover the strangest birds.

With its grey feathers, yellow eyes, orangey bill, and long, knobbly legs, the shoebill stork looks like a relic from the dinosaur age.

Named for its clog-shaped beak, shoebills are large birds, usually measuring 1-1.5m from the tip of their head to the bottom of their feet. With a 30cm, hooked beak, and a 2.4m wingspan, they’re certainly not the type of birds you’d want to upset if you encountered them in the wild.

A shoebill’s head is proportionally bigger than the rest of its body—mostly due to its oversized beak. The foot-long bill is around 12cm wide and has sharp edges and a pointed hook at the end used for catching and impaling its preferred prey, lungfish. Shoebills have also been known to use their beak to catch turtles and even baby crocodiles!

Shoebills also have long legs and large feet, which they use to walk on the vegetation of the swamps and marshes where they live. The population is classified as vulnerable, with its habitat across East Africa (from Ethiopia and South Sudan to Zambia) being destroyed for a myriad of reasons. The birds themselves are sometimes also killed as food, or due to people believing they’re a bad omen. As of 2018, there were 3,300–5,300 shoebills left in the wild, with a population trend of ‘decreasing’.

Shoebills are quite docile around humans, although they are known for their ‘golden stare’ – so if you ever see one in the wild, be prepared for the strangest staring contest of your life.

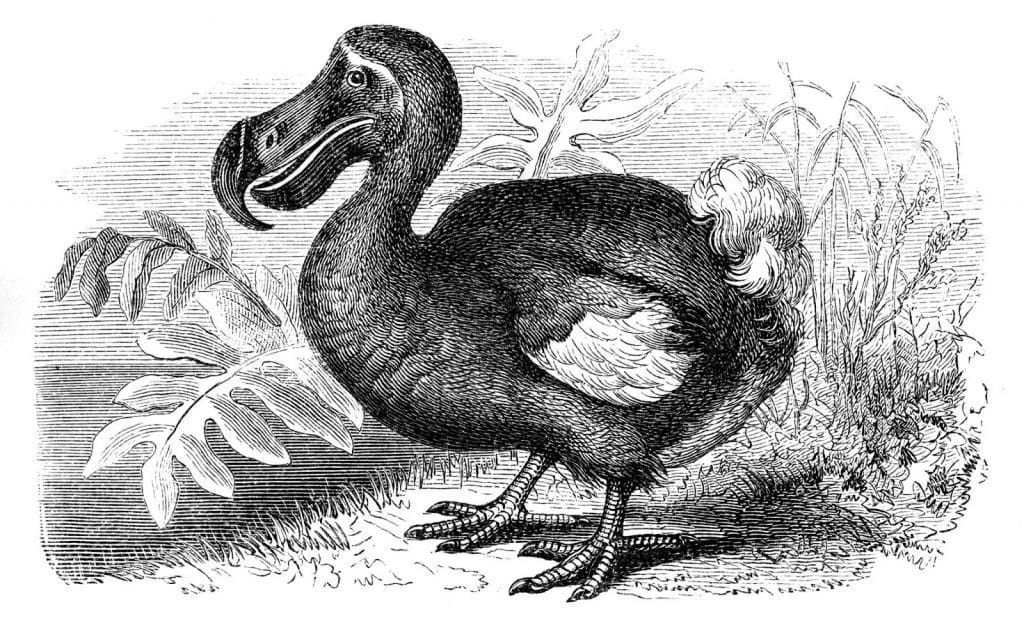

Famed for being the prime example of human-induced extinction, the dodo lived on Mauritius Island during the late 1500s. By around 1681, this large, flightless bird was extinct, mainly due to the Dutch colonists that arrived on the island—and the animals they brought along and introduced to the land.

Part of the Raphidae family, dodos once grew to around 90cm, had tiny wings, and strong, flexible knees for manoeuvering around the rocky island. They had grey-blue feathers, a big head, hooked beak, and they weighed around 20kg.

Pre-colonisation, the dodos lived on the island in relative peace with plenty of food, water, and no natural predators. The arrival of humans on the island catalysed their extinction, though it’s not collectively agreed how. There are a few suggested reasons, including:

Although they can no longer be found in the wild, museums around the world—including the British Museum—have relics and fossils of the bird.

It looks like an owl, it sounds like an owl, it’s nocturnal like an owl—but is not an owl. It’s a tawny frogmouth.

Measuring around 40–50cm long and wrapped in brown/grey plumage, the tawny frogmouth’s colours exactly replicate that of tree branches – with a similar textural appearance too. They have yellow eyes, wide mouths (hence the name), and curved beaks. The one thing that differentiates them from owls are their claws. Where owls have sharp talons, capable of catching prey, tawny frogmouths have comparatively weak claws.

They wait patiently for their prey to wander into their line of sight, swoop down, and then return to their branch. They eat insects, including worms and beetles.

Tawny frogmouths are found all over Australia, in a wide range of habitats. At night, if you are lucky enough to spot one, they can usually be found sitting motionless on a tree branch. The birds often travel in pairs, and a breeding pair will often stay in the same territory for more than 10 years.

As they are nocturnal, the birds are known to sometimes wander into the road, if they see insects being lit up by car headlights. If you’re driving in a regional area, go slow, and watch out for tawnys (and other animals).

Next time you go out for a nature walk, look up!

Touting the ‘most dangerous bird in the world’ title, the cassowary is not a bird you’d want to trifle with.

Standing up to 1.8m tall, this flightless 70-80kg bird belongs to the genus Casuarius. There are three types of cassowaries, each with multiple races.

All three cassowaries have shiny black plumage on their bodies, a blue head, and a bony helmet (casque) for protection. The Dwarf and Southern Cassowaries have blue necks, whereas the Northern Cassowary has an orangey/yellow neck.

So, what makes them so dangerous? If you look down, you’ll soon work it out. Cassowaries have very powerful legs, and on the ends of those legs, are long, scary claws that can deliver a lethal blow. Their longest claw is 12cm, which can slash through human (and animal) skin. They are very protective of their young, especially during feeding time, so if you do see one, back away slowly and put something over your front for protection (like a backpack). Cassowaries can run very fast too—up to 50km an hour! Cassowaries eat berries and small animals.

The Southern Cassowary is listed as endangered, mainly due to habitat loss and degradation.

We may not be ornithologists (bird experts), but we are chemicals management experts—and we’re here to help! Whether you need a hand with your Safety Data Sheets (SDS), chemical labels, Risk Assessments, or chemicals handling, we can swoop in to assist! Give us a call or (03) 9573 3100, or email us at sa***@*******ch.net.

Sources: