In Australia, food waste is a major problem: it costs the economy about $20 billion each year. This equates to approximately 7.3 million tonnes of food being wasted, which is 300kg per person or one in five bags of groceries.

Food waste is also one of the biggest emitters of greenhouse gases (GHG). In the global market, if food waste were a country, it would be the third largest GHG emitter behind the US and China. In Australia, food waste accounts for more than five percent of Australia’s GHG emissions.

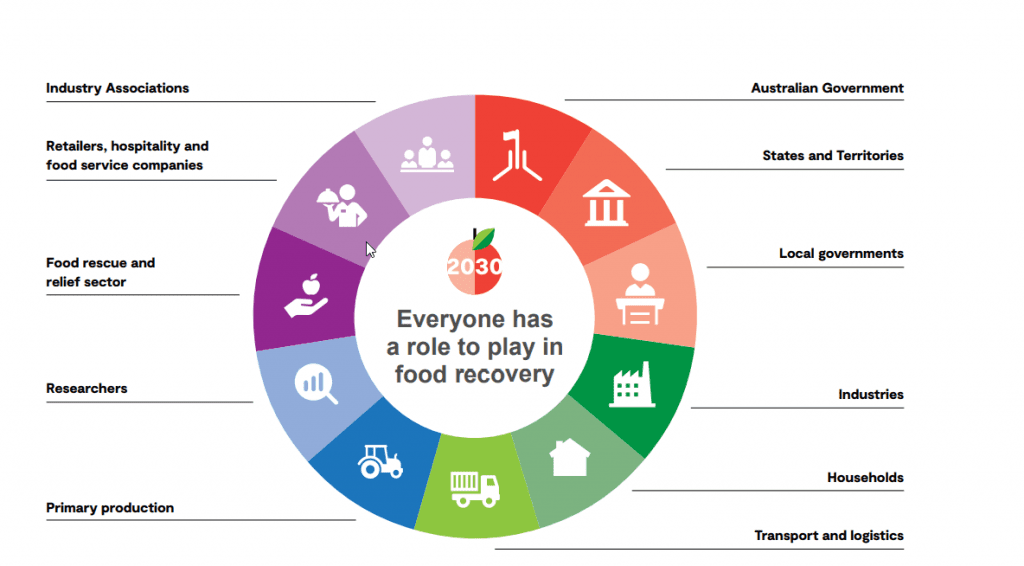

In accordance with the UN’s Sustainable Development goal 12.3, the Australian government has set a target of halving its national food waste by 2030. A roadmap has been put into place to reach this target by the deadline with each sector allocated a range of roles and responsibilities. According to the roadmap, ‘over one-third of food waste occurs at the household level with most going to landfill. [This represents an] opportunity to raise awareness for behaviour change’.

One of the points raised in the National Food Waste Strategy: Halving Australia’s Food Waste by 2030, which details how Australia is going to reach their target, is the ‘increased adoption of home composting and worm farms’.

While this change in consumer behaviour seems simple enough to adopt, the myriad of ways to compost, makes it difficult to know where to start. Probably best to follow the wise advice of Maria from The Sound of Music and ‘start at the very beginning’.

Composting is the breakdown of organic matter, which is anything that was once living. This matter is broken down into two categories: green and brown matter. Green matter includes green plant matter (grass clippings, old flowers, some weeds), coffee grounds, tea leaves, crushed eggshells, and fruit and vegetable scraps. Brown matter includes materials such as paper and cardboard, straw, dry leaves, woody prunings and sawdust (only from untreated wood).

Is there anything you can’t put in your compost?

This mostly depends on the compost system you are using, but there are some items that should never go in, regardless of your system. For example, pet droppings (except from chickens), diseased plants, weeds with seeds, baking and glossy paper, treated wood, and cooking fat.

Most smaller home composters advise users not to put meat or fish (bones) into their bins because they could attract rats. Some council compost bins accept meat and fish as well as dairy products (which are also not commonly put into normal household compost bins). Some people don’t put any citrus, garlic or onions into their home composts as these are believed to repel earthworms which are a vital part of composting and the garden as a whole.

Aside from helping Australia reach the UN Sustainable Development Goal, composting is beneficial for the environment. When food waste is thrown into the rubbish bin and sent to landfill, it releases toxic methane gas. For example, if 180kg of food waste is sent to landfill, it produces 15.3kg of methane gas.

A powerful GHG, methane gas is about 28 times more potent than carbon dioxide when it comes to warming the Earth on a 100-year timescale, and more than 80 times more potent over 20 years.

Although there is not a lot of methane in the air, due to its chemical shape, it is highly effective at trapping heat—which means a little goes a long way. Scientists believe about 60% of the methane in the atmosphere today comes from human-related sources. Composting stops (or significantly reduces) methane production, through the process of aerobic respiration.

As mentioned previously, there are a multitude of composting methods. The first thing you need to decide is what kind of compost bin would suit your lifestyle. Questions that will guide your choice include: Do you have a garden? Do you live in an apartment? Do you have a balcony?

If you have a garden, a compost bin or tumbler would probably suit your space.

Although they vary in size and appearance, most compost bins are large and black with a flat-topped cone shape with the lower end opening directly onto the ground/soil.

A compost tumbler consists of a rotating horizontal drum attached to metal legs. The built-in rotation of the tumbler makes it easier to use, although it is more expensive than the compost bin, which requires you to toss the compost yourself, with a fork or something similar.

If you have an apartment with a small or no garden, a worm farm is a good option.

You begin by building or buying a worm farm, and then buying worms to put into it. Your starter kit should contain at least 1000 worms of different varieties, including Red Wigglers, Indian Blues and Tiger Worms.

Keep your worm farm in a protected area, away from heavy sun and rain. Line the tray with moist paper, release the worms and their bedding, and cover with more moist newspaper. Let your worms acclimate for a week before feeding them. Your worm farm will produce liquid fertiliser and worm casts, which are both great for your plants. Your worm population will double every 2–3 months.

Another option for a smaller space is the Japanese invention known as a Bokashi bin. Bokashi bins pickle your waste. The kit typically consists of two bins and a substance called Bokashi bran. Everything goes into your Bokashi bins: fruit, vegetables, cheese, meat and fish (cooked or uncooked), tissues, flowers, tea and coffee (leaves, grounds or bags) and bread.

Once your bin is full, simply sprinkle some Bokashi bran on top, seal the lid, and leave it for a few weeks. It won’t smell bad, except for the slight smell of pickling. The bins are portable and can be placed outside if you’re not a fan of the smell of fermentation.

While you wait for your first bin to mature, you can get started using the other bin. Bokashi bins have a tap on the bottom from which you can release a stream of ‘liquid gold’ that can be diluted and used to water your plants. It’s full of nutrients and good microbes. After three weeks, you can open your bin and tip the contents into your compost bin or into your garden.

The other option is ShareWaste, an Australian website and app that allows you to connect with people who already have composting facilities, so you can compost without necessarily doing it yourself.

Compost is a small but very powerful way you can help the environment.

Chemwatch is here to help

By joining the composting movement, you’ll be doing your bit to reduce the amount of dangerous chemicals in the atmosphere. Chemwatch helps people across the globe to manage, use and dispose of chemicals safely. Many chemicals should not be inhaled, consumed or applied to skin. To avoid accidental consumption, mishandling and misidentification, chemicals should be accurately labelled, tracked and stored. For assistance with chemical and hazardous material handling, SDS, labels and large quantities of chemicals, contact Chemwatch on (03) 9573 3100.

Sources: